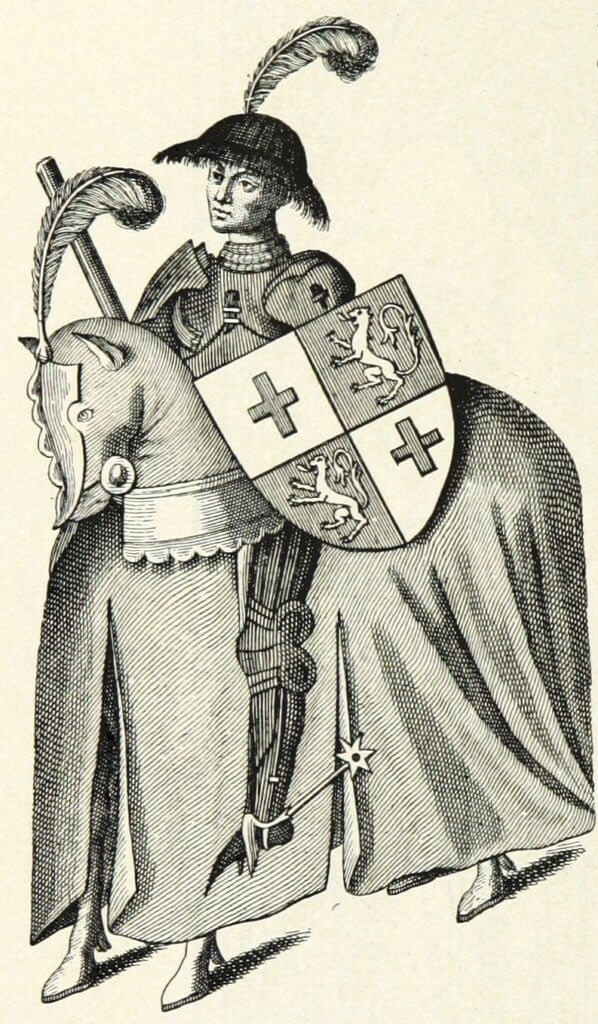

The coat-of-arms of Rev. John Greenwood (pictured), rector of Brampton, Norfolk County, England, from 1620 to 1663. According to English laws of heraldry, armorial bearings are the property of an individual, not everyone with the same last name.

By William Armstrong Crozier

Reprinted from William Armstrong Crozier’s originally titled “The Use and Abuse of Armorial Bearings,” an article appearing in The Delineator (March 1905), pp. 426-428.

The science of heraldry is of very ancient origin. We learn from both sacred and profane history that it was the custom from the earliest ages for various communities to adopt some distinctive device, which, when depicted upon their standards, afforded a ready means of identification during the stress of battle. These insignia were at first confined solely to nations, but, in the course of time, similar devices were adopted by military commanders, and their example was followed later on by individuals.

Sylvanus Morgan, one of the early writers on heraldry, and a gentleman gifted with a very vivid imagination, assigns the first coat armor to Adam, to whom he give plain shield gules, over which, on an escutcheon of pretence, he bore the silver shield of his wife Eve. After the fall, he says our great ancestor placed upon his shield “a garland of fig leaves, which his son Abel quartered with argent, an apple vert, in right of his mother Eve. ” As he makes no mention of Cain, we must naturally conclude that the antediluvian Herald’s College had refused to recognize his right to coat armor, probably on account of his unbrotherly conduct.

Leaving these questionable records of ancestry, we come to a period from which it can legitimately date as a science. This is certainly not earlier than the twelfth century, as the first well-known century, as the first well-authenticated example of an heraldic example of an heiress charge adopted by an individual is found on the seal of Phillip, Count of Flanders, bearing date 1164, which device is a lion rampant. There are manuscripts extant to the thirteenth century in which the Saxon kings are depicted with arms duly charged upon their shields, but the chroniclers of that period have ever been given to anachronisms, when no authentic record has been found before them. The scribes of seven centuries ago are ably followed in their absurdities by many armorial writers of the present day.

It has long been a matter of doubt when the bearing of coats of arms first became hereditary. Armorial bearings were probably, like surnames, assumed at the will and pleasure of the bearer, but the introduction of individual bearings must be attributed, in a great measure, to the institution of jousts or tournaments.

Single figures, usually of an animal, constitute the earliest charges, but toward the close of the twelfth century, so many claimants to armorial bearings appeared that extra charges were placed on the shields to avoid confusion.

When the College of Heralds was established in England in 1483, its business was to register Grants of Arms, and to see that such distinctions were not borne illegally; in other words, to bring order out of chaos that must have existed for a long time. From 1528 to 1704, its officials made periodic Visitations to the various counties for the purpose of registering pedigrees, confirming and granting coats of arms. This was a very necessary precaution, inasmuch as many of the gentry of that period had little hesitation in appropriating the coat of arms of another person as have the coat-armor pirates of today. The Herald, making due proclamation of his purpose, entered upon his roll the names of those who appeared before him and proved their pedigree, and he also acted as arbiter in all disputes.

It has long been a matter of doubt when the bearing of coats of arms first became hereditary. Armorial bearings were probably, like surnames, assumed at the will and pleasure of the bearer, but the introduction of individual bearings must be attributed, in a great measure, to the institution of jousts or tournaments.

Single figures, usually of an animal, constitute the earliest charges, but toward the close of the twelfth century, so many claimants to armorial bearings appeared that extra charges were placed on the shields to avoid confusion.

When the College of Heralds was established in England in 1483, its business was to register Grants of Arms, and to see that such distinctions were not borne illegally; in other words, to bring order out of chaos that must have existed for a long time. From 1528 to 1704, its officials made periodic Visitations to the various counties for the purpose of registering pedigrees, confirming and granting coats of arms. This was a very necessary precaution, inasmuch as many of the gentry of that period had little hesitation in appropriating the coat of arms of another person as have the coat-armor pirates of today. The Herald, making due proclamation of his purpose, entered upon his roll the names of those who appeared before him and proved their pedigree, and he also acted as arbiter in all disputes.

According to English laws of heraldry, armorial bearings are the property of an individual, descending to his children and their children. It is the exclusive property of the one who either received it by grant or proved his prescriptive right to it. If it is attained by a grant of arms, the lineal descendants, not the collateral relatives, may pretend to it. The brother of a grantee is no more entitled to the use of the same arms than a complete stranger. Maternal descent from a gentlewoman does not give the right to coat of armor to the descendant of a man not having inherited from his male ancestor. If a man without armorial bearings marry an heiress, he cannot make use of her arms, for having no escutcheon of his own, it is evident he cannot charge his shield with her arms; neither would their issue, being unable to quarter, he permitted to bear their maternal coat. This is a rule frequently violated in America.

The question whether a title to armorial bearings can be claimed by prescription has of late been the subject of much controversy among English authorities. By prescription has been the subject of much controversy among English authorities. By prescription is meant the use of a coat of arms for three generations, or at least one hundred years. The validity of this rule is of much importance of the heraldic families of America. For the authority in support of prescriptive usage, we have only to turn to the Heralds themselves, as it is unquestionable that the Heralds during the early Visitation periods did not recognize arms upon the sole strength of usage for a certain length of time. Hundreds of coats of arms were recorded without alteration and without confirmation, and as late as 1668, a time when heraldic abuses were manifold, we find William Dugdale, Garter King of Arms, writing as follows:

It is incumbent that a man doe look over his own evidences for some seales of armes, for perhaps it appears in them, and if so and they have used it form the beginning of Queen Elizabeth’s reigne, or about that time, I shall then allowe thereof, for our directions are limiting us soe to doe, and not a shorter prescription of usage.

Here we have the highest heraldic authority in the Kingdom, Garter King of Arms, expressly stating that a man is justified in using a coat of arms, provided it has been in use by his family for one hundred years, or about given at a time when the Heralds’ Visitations were still in force. This is admittedly the old practice of the English Heralds, and is strictly analogous to common sense and the rules of common law. At the present day, Dugdale’s ruling is followed by Ulster King of Arms and the Scottish Heralds, who will confirm by patent any arms which have been continuously borne for three generations, or at least one hundred years.

During the Revolutionary and Civil Wars, many public and private records, bearing seals and impressions of arms, were destroyed. Seals are of all records those on which the greatest reliance can be placed, for being contemporary witnesses, no doubt can exist of their historical value. These records were frequently the only proof extant that certain families were entitled by inheritance to coat armor, and as the descendants of many of these families have continued to use a coat of arms, the prescriptive authority for their doing so is important.

Between the years 1700 and 1729, a Boston carriage maker, by the name of Gore, compiled a record of the coats of arms of his customers. The collection consists of ninety-nine coats painted by hand, and is known as the “Gore Roll of Arms, ” being the oldest manuscript record of arms in America. During the latter part of the eighteen century, the heraldic charlatan made his appearance, furnishing to wealthy patrons arms found at random in some book, or, more frequently, in the imagination of the inventor. These bogus heralds has no hesitancy in attaching their names to their work; and it may be well to state that any painting of arms that has upon it the name of Thomas Johnson, John Coles or Nathaniel Hurd should be viewed with high suspicion.

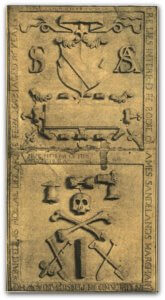

The old graveyards afford hundreds of examples of the early use of coat armor in this country. One of the most remarkable—remarkable not only for its state of preservation, but for its unique design— is the stone covering the grave of James Sandelands (pictured), of Upland, Pa. This representation is devoid of the usual helmet and lambrequin, which is in evidence on the Reynolds tombstone found in the old cemetery at Bristol, Rhode Island.

In America we have no institution analogous to the College of Heralds; the consequence is, that there are more assumptive arms borne in America than anywhere else. It is not overestimating when we say that at least seventy-five percent of the arms engraved on notepaper today are fraudulent. The bearers of such arms are not so much to blame as the self-styled heralds who supply them; the greatest sinners in this respect being the heraldic stationers, whose chief recourse is a Burke’s Peerage or Armory, and as nearly every ordinary name may be found in their pages, no customer is permitted to leave unsatisfied.

Irrespective of the fraudulent use of arms, heraldic rules are deliberately set aside by bona fide users. According to the laws of heraldry, an unmarried woman must not bear the arms of her ancestor within the shield of a bachelor; neither is she permitted the use of a crest. This rule is defied, not so much through the ignorance of the bearer, as from the desire to display every heraldic device belonging to the male members of the family. Not only good sense, but good taste, demands that we use only that to which we are entitled. To portray correctly the arms of a spinster, they should be placed within a lozenge; and as a woman is prohibited from using a crest, its display is incorrect.

The crest is the highest part of the ornaments of a shield of arms, its origin probably being more ancient than that of the other heraldic bearings. The right to wear them was considered a very great distinction in the early days of heraldry, because they could only be acquired by those who had, as knights, seen actual service in the field. We frequently see a coat of arms that one is his own and the other is his wife’s crest. But as ladies can neither bear, inherit or transmit them, we may confidently assume that this is a case of home-made heraldry. The only possible right that a man can have to more than one crest, is where more than one has been granted to his paternal ancestor. Although a man may be entitled to numerous quartering, he has no right whatever to any of the crests pertaining to quartering in virtue of his inheritance of them through marriage.

It must be borne in mind that the above pertains only to English heraldry, the American families of German or French descent abiding by the laws of those countries which differ from the English rules in many particulars.

The tombstone of James Sandelands in Pennsylvania includes a coat of arms.

The inscription reads:

HERE LIES INTERRED THE BODIE OF JAMES SANDELANDS MARCHANT

IN UPLAND IN PENNSYLVANIA WHO

DEPARTED HS MORTAIL LIFE APRILE THE 12 1692 AGE 56

By the aid of coat armor the descent of a family may be ascertained, and it is necessary, therefore, that it be used in a legitimate and appropriate manner. In America, the indiscriminate use of crests and shields, without rule or method, is much to be deplored. The display on a carriage of a crest alone was senseless; both crest and shield should be used, for the reason that so many families bear the same crest, they can be distinguished only by the addition of the escutcheon. On one’s stationary or silverware it is permissible to use a crest, or a crest and shield.

An erroneous impression exists in the minds of many persons, not only in America, but in Europe as well, that the bar sinister is mark of illegitimacy, and the belief is so general that we even find an author applying it as a title to one of his best known stories. As a matter of fact, there is no such thing as a bar sinister—it is an heraldic impossibility. We have the “bar,” which is an honorable ordinary, formed by two parallel lines occupying a fifth part of the shield. The mark of illegitimacy is the baton sinister, which is borne over all the other charges, making it appear as though the shield had received a long narrow blot running from right to left. For the descendants of royal blood, the baton is composed entirely of metal. According to some of the old authorities, this mark should be borne by the descendants of the natural son until the third generation, when they are permitted to relinquish it and assume the original paternal coat.

It may be asked, of what use is the revival of a science smacking the days of the mailed knight and the donjon keep? If the study of heraldry served but to pander to the vanity of a few and to excite the envy of many, its teachings would be useless—in fact, pernicious. Fortunately it has higher and nobler purposes to serve. Not only to the antiquary and archeologist are its teachings valuable, but hardly a day passes that some branch of the science is not brought to our notice. The writings of our oldest Gothic architecture lose a good deal of their interest, and Gothic architecture tells no story and painting but an incomplete one, without some acquaintance with heraldry.

As descent form an armigerous ancestor is popularity supposed to denote gentle blood, those who cannot lay claim to this distinction may derive comfort from the words of Chaucer’s Elf-Queen, who says that it is not ancestry, but”gentil dedes” [gentle deeds] which make the “gentil man.”