By Gary R. Toms and James Pylant

Copyright © 1998, 2006, 2017—All rights reserved

Do not post or publish without written permission

Reprinted and revised from “Taliafero is Toliver: Surnames Sound a Challenge,”

American Genealogy Magazine, Vol. 13, Nos. 1 & 2

Names are at the heart of genealogical research. Most family historians are well aware that surname variants are not to be overlooked in research. Some routine changes in spelling can be anticipated and are easily recognized as variations of the surname of interest. Examples would be Layfoilet or Lafarlett for LaFollett.

A slightly different situation occurs when an older spelling is retained, but the pronunciation changes. This produces the challenge of surnames for which the spelling does not match the pronunciation. This can mislead a researcher, or even seriously impact on the success of those who do not take it into account. Surnames in this category are the focus of this article.

Two circumstances, in particular can produce situations which may be confusing or which can stymie the researcher. Retaining an original spelling and its “foreign” sounding pronunciation was difficult for most immigrants. To Americanize a surname, one of two things might happen. The pronunciation might be changed to match the spelling, or the reverse might be true. An entirely new spelling was sometimes adopted to keep from losing the preferred pronunciation. In some instances, both spelling and pronunciation were Americanized.

Thomas W. Jones’s success tracing an elusive ancestor came after learning the surname Overton was originally Howerton. “Cultural or ethnic variations in the sounds of certain letters also result in substitutions that modern genealogists simply do not expect . . . .,” Jones stated.1 Similarly, an Oskisson genealogist now suspects that her family’s name was originally spelled Hoskinson.

The situations which lead to surnames with spelling quite varied from the pronunciation can generally be attributed to one or two occurrences:

- When people moved from one area to another, the sound of their surname may have been retained while the spelling changed to reflect the language of the new residence. These situations are relatively easy to determine, and most researchers can easily deal with this by being alert to spelling variations.

- In a reverse situation, the sound may change, perhaps even dramatically, while the original spelling from the language of origin is retained. Two outstanding examples of this are Mainwaring, as mannering, and Mieriotto, pronounced mur-oh-tee.

This article focuses on surnames from both occurrences, names for which the pronunciations and the spelling do not quite match. “Particularly in a literate age, you can get quite a bit of gap between spelling and pronunciation [of surnames],” according to Paul Roberts, a former professor at the University of Leeds, England, now engaged in research of the origins of certain surnames found in the Appalachian Mountain region. He uses Beauchamp as an example, pointing out that despite the spelling it pronounced beech-um.2

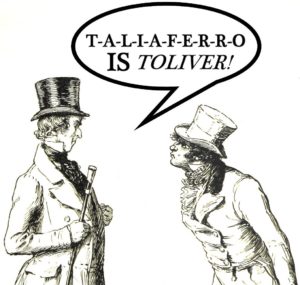

The situation often comes full circle, when a spelling develops to reflect the actual sound of the name, leaving the original spelling behind. This is what occurs when a name like Talliferro/Taliaferro, pronounced tah-li-ver, changes to Toliver or Tolliver. A researcher may first encounter the name under such a spelling, which clearly reflects its pronunciation. That researcher may be unprepared for the original spelling when it is encountered later.

For the unwary researcher, not considering the possibility that a name may have a spelling distinctly different from its sound can be harmful. It can result in stonewalls when the surname is not found in an expected record source. The name may actually be there, but in a way that the researcher does not recognize. In a worst case scenario, the researcher might flounder for months or even years before being able to bridge the gap between the newer, phonetic spelling, and the original spelling in another locality. Another problem occurs when the name is followed to another locality where it occurs interchangeably under the modified (familiar) spelling and the original spelling—as well as variations of both, of course. The researcher may never feel confident that all records have been found. Worse yet, he or she may miss an entire segment if unaware of the original spelling.

This is especially likely to be the case when the researcher begins with a changed spelling closely reflecting the sound of the name, and tries to follow it back to a locality where the original spelling dominated. Consider, however, researching Tolliver in East Tennessee, in a family whose spelling had changed to conform to pronunciation. The unprepared researcher might lose the family when the records in a Virginia locality only show it as the original Taliaferro.

Certain languages, with spelling rules very different from English, can provide sounds close to that language. German names are especially prone to this. Behle sounds like Bailey; Gehl is pronounced gale, and how about Leimkuhler? It is pronounced lime-cooler. Other examples are of French origin, such as the surname Allier, which has variations in both pronunciation and spelling. While retaining the original spelling, it may be pronounced as the Anglicized all-yer. Others vary the pronunciation to al-leer. Still others with that surname chose to change the spelling to resemble the original French pronunciation, hence the variant Allyea.

In the United States, the French Du Bois, while retaining its old spelling, has dropped du bwa in favor of an Americanized sound. A verse in a clever poem written for the DuBois Family Association reminds us of the New World pronunciation3

‘Tis no longer du Bwa as so many suppose

And it is not Du Boys, and of course not Du Boze

Du Boy is not right, nor is Du’Bois correct,

For the accent is not where some people suspect

Please read this out loud so the sound of your voice

By this rhythm records that our name is Du Bois

In some instances, even with names which appear to be of English origin, the sound and the spelling can take divergent paths. This can easily happen when an old pronunciation continues while the spelling evolves. Toms, generally pronounced tahmz and related spelling of Tomes, are pronounced in some localities as toemz or toomz, which are distinctly different. The latter pronunciation is what one would expect from Toomes, or Tombs, but not Toms.

The situation really becomes perilous when the research leads to a locality where the name has its original spelling, and another surname occurs in the records which appears to match the sound of the name, but actually is pronounced differently. If a researcher focused on Bales ancestry delves into the records of certain east Tennessee counties, the surname Bayles appears to be a match. It is not, however. In that area, it is pronounced bay-less and is sometimes found with that spelling, as well. In contrast, Beals is pronounced bales in that area, even though the spelling may suggest beels.

The researcher must also be alert to the fact that some of these pronunciations are local variations. The same surname, with the identical spelling, may have a more common pronunciation in Middle or West Tennessee and points south from there; Jordan as jurr-den and Toms as toomz are good examples of this. Each of these pronunciations is unique to a certain area, and probably the areas to which families moved from there. Jurr-den, for example, is the pronunciation in Middle and West Tennessee and points south from there; Jordan is pronounced jor-dun in most other areas.

It is our purpose in this article to challenge your thinking, to give you different ways of looking at surnames involved in your research, beyond the simple variations imposed by the spelling tendencies of various clerks. Such a mode of thinking may help you avoid some pitfalls when dealing with this type of surname situation. To assist you in this process, we have prepared a list of such names to accompany this article. For maximum benefit, you may wish to read aloud the phonetic pronunciations provided in the list. This same technique can be helpful when you encounter an unfamiliar surname: say it aloud, several times, changing the accented syllable or the vowel sounds. Listen for the sound of a name which is familiar to you. That may suggest an alternative spelling to include in your research. We encourage readers to study this list, and think carefully about the spelling, and pronunciation of the surnames involved in their research. The list of examples help the researcher become familiar with the type of surnames discussed in this article. This is by no means a complete list. Many readers will be aware of others which fit the criteria described. We encourage you to share those. If enough are received to warrant it, a supplemental list may be published.

PLEASE NOTE: These examples have been collected by the authors over a period of 37 years, and reflect many different situations. Especially be aware that some pronunciations are localized, and the surname occurs under a more common pronunciation elsewhere.

- Allier = all yer, al leer

- Althorpe = al thrup

- Ansderau = an drews

- Askey = harrisky

- Athey = ath uh

- Bacot = buh coat

- Bakerstere = baxter

- Baldwin = boll den, ball den

- Balfour = bal fer

- Barbee = bob bee

- Barham = barm

- Barfield = bare field

- Battaglia = buh tal yuh

- Baughman = bow man

- Bayles = bay luss

- Beall = bell

- Beals = bales

- Beaucattie = byoo kay dee

- Beauchamp = beech um

- Beaufoy = boffy

- Behle = bay lee

- Behrens, Behrends = bear enz

- Berkeley = bark lee

- Blount = blunt

- Bodde = bow dee

- Boehner = bay ner

- Boemer = bay mer

- Bohm = baum

- Bouchier = boxer

- Boutiette = boo tee yay

- Bownds = bounds

- Brasseur = brassy

- Buras = boo ross

- Burrell = burl

- Burrow = burr

- Cahusac = kuh zack

- Caughman = cawf mun

- Caughron = cock run

- Chapelle = supple

- Chapuis = sho pee

- Chicheley = chess lee

- Childress = child erz

- Cholomondley = chumley

- Cockburn = co burn

- Colbaugh = cal bow

- Colquhoun = ca hoon

- Coquerel = cock ril

- Cordes = codes

- Costello = cost uh low

- Cowe = coe

- Cowper = cooper

- Coylton = cull tun

- Creamer = cray mer

- Crough = crow

- Crowe = crauw

- Crowfoot = craw ferd

- Cruwys = crews

- Cukjati = shuh ka tee

- Cusenbary = koosh en bree, koozen berry

- Dalziel = deal, dee ell

- Darlingscot = darscot

- Death = deeth

- De Leow = dill oh

- De Ville = da veel

- De Vore = dee voe

- DeLoach = dill oh

- Dier = deer (not dyer)

- Dieudonne = dud ney

- Donen = dah nen

- Donne = dunn

- Dubois = doo b’wah, doo boyce

- Duchamp = doo shawn

- Dupuis = du pee

- Eames = aimz

- Eleazer = el ee ay zuh

- Eliason = e lee uh son

- Eyre = air

- Farve = fav er

- Faucher = foo shay

- Featherstonehaugh = fan shaw, featherston hoar, featherstone haw

- Fiennes = fines

- Fjoser = fee oh ser

- Fohn = fone

- Fooshee = fo shay

- Frieh = free

- Fullwood = fullard

- Gehl = gale

- Geiger = gee guh

- Gein = geen

- Giesenschlag = geezin slaw

- Gilbreath = gil breth

- Girardeau = jerry doe

- Gotham = goat um

- Gochener = go nower

- Goupe = guppy

- Grandtully = grant lee

- Grosvenor = grove ner

- Guyn = gwin

- Hatfield = hatfull

- Hebert = a bear

- Hechter = hesh tay

- Hoar = harr

- Hockenhull = hock nell

- Hoeffer = hay fuh

- Hoescht = herkst

- Hogg = hoag

- Horger = her guh

- Hough = huff or hoe

- Housley = ow slee

- Huger = you jee

- Hulme = hewm

- Iahn = yahn

- Jacques = jakes

- Jaeckle = yack lee, yeck lee

- Jameson = jim er son

- Jahnz = Jants

- Jeffries = jeff ress

- Jordan = jur dunn

- Jung/Jongh = yung

- Keats = kates

- Keitt = kit

- Kerr = carr

- Kinard = ky nud

- Knoepker = kuh nep ker

- Koch = cox

- Koenig = king

- Kolb = culp

- Kuch = cook

- Kuykendall = kirk en dahl

- Lachey = luh chay

- Lassiter = last er

- Le Cog = lay cock

- LeFavre = luh fave

- Lefever = luh fave

- Lehne = laney

- Lidia = lie dee

- Leicester = lester

- Lied = leed

- Livesay = le va see

- Logiudici = luh jah dus

- Loizeaux = lu wah zo

- Luckhoo = luh koo

- Luenstein = liv ing stone

- Lutyens = luh chens

- Lyster = lester

- Machen = macken

- Mainwaring = man er ing

- Mantooth = mon teeth

- Marquis = mark wiss

- Matous = may tosh, mattice

- Maurice = morris

- Maury = murr ee

- Mayberry = may bree

- McGill = mackle

- McGough = muh gew

- McGrath = Mc graw

- McKey = mac kee

- McLeroy = mack ul roy, muck ul roy

- McLin = mack lun

- Meador = medd uhs

- Melancon = mel lawn sawn

- Meetze = mets

- Meierotto = murr oh tee

- Menzies = ming iss

- Merrill = murl

- Moberley = mob lee

- Murchison = murk e son

- Murdaugh = murder

- Neuffer = ny fuh

- Ouzts = oots

- Partain = parr tun

- Peil = pale

- Peirce = purse

- Pelletier = pelter

- Peulen = pauline

- Peyre = peh uh

- Pieniadz = penny ants

- Poaches = po shay

- Plowden = plew dawn

- Porcher = puh shay

- Pylant = pe lawnt, paw lunt

- Radford = red furrd

- Ralph = rafe

- Randolph = ran duff, ran dal

- Reagan = ree gunn

- Riedel = rey dell

- Rives = reeves

- Robertaill = robe it tie

- Rubarth = roo bert

- Salisbury = solls bree

- Schachte = shack uh tee

- Scheuch = shoyshh

- Schlumberger = schlum ber zhay

- Shore = shaw

- Shough = shuff

- Speight = spate

- Speissegger = spize ay juh

- St. Clair = sink lur

- St. John = sin jun

- St. Paul = sem pul

- Taliaferro = tal liv er

- Tarpley = taplee

- Tatham = tate um

- Teuscher = toy sher

- Tignor = tick ner

- Toms = toamz, toomz

- Towle = tole

- Tuomey = too mee

- Tuthill = tuttle

- Urquhart = ur cut

- Ussery = ush uh ree

- Van Dien = van dean

- Van Slaigh = van sly

- Van Kleeck = van clake

- Walling = wald in

- Waters = waiters

- Whitworth = whitter

- Wilde = vil duh, will dee

- Worcester = woost er

- Yedon = yay den

NOTES AND REFERENCES

- Thomas W. Jones, “Howerton to Overton: Documenting a Name Change,” National Genealogical Society Quarterly, Vol. 78 (September 1990), No. 3, p. 171.

- Paul Roberts to Gary R. Toms, 1 October 1997.

- Written by Floyd Reading DuBois (1878—1952), the poem appears on the DuBois Family Association’s website. Excerpted with permission of Terry DuBois, webmaster.