“Most southern families that do ‘have Indian blood’ are descendants of the ‘civilized’ tribes of the southeast, those that had extended cultural contact with Europeans as early as the 17th century.”

By Winston De Ville

Copyright © 1987, 2005—All rights reserved

Reprinted from American Genealogy Magazine, Vol. 2, No. 3

When this writer began doing research on his own family history, his grandmother told him that “the first De Ville in Louisiana married an Indian girl.” Such tales are part of the lore in numerous families, but proved untrue in this case. As a matter of fact, relatively few Indian-European marriage occurred in the Gulf South.

The truth is that Gulf Coast Indians, during the earliest days of the colony, were not highly civilized; the southwest Louisiana Attakapas tribe, for example, had been cannibalistic prior to French colonization. After colonization, Indian slavery was not uncommon.

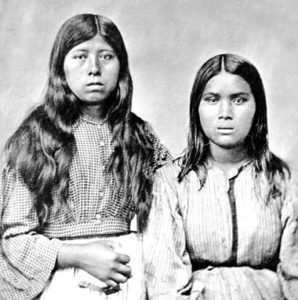

Most southern families that do “have Indian blood” are descendants of the “civilized” tribes of the southeast, those that had extended cultural contact with Europeans as early as the 17th century. One such tribe was the Creek Indians. By the time the Deep South became part of the United States in the late 18th and 19th centuries, more than one generation of mixed Indian and Anglo-American descendants had been born. Their genealogies are, however, most often elusive; researchers generally rely on federal records at the National Archives to trace such lineages.

Before describing a document of considerable importance for Anglo-Indian research, we want to make it clear that it was ancestors who called children of those “mixed” marriages “half-breeds,” a term we would not use except in a quotation.

The document referred to is titled, “Application of Sundry Half-Breeds of the Creek Nation to Sell Their Reservations of Land in Alabama: 1826.” Almost all of the 45 heads-of-households have surname of typical southern families, and it is clear that they were highly-respected member of local society. The record describes the land in some detail so each owner can be located with a great deal of precision. The original publication is in American State Papers: Public Lands, Vol. 4 (1832; reprinted 1994). This ten-volume set is found in the genealogical collections of most larger libraries.