By JAMES PYLANT

Copyright © 2005, 2019

Under the provision of the Curtis Act (1898),1 the Department of the Interior, Commissioner of Five Civilized Tribes, recognized “citizenship by intermarriage” in the Cherokee Nation. To qualify, an applicant had to sufficiently prove that he or she was married in accordance with Cherokee law, and who at the time of the marriage was a recognized citizen by blood of the Cherokee Nation. The Commissioner of the Five Civilized Tribes then compared the applicant’s information with that shown on the Cherokee tribal roll of 1880 and the Cherokee Census Roll of 1896 as an intermarried citizen of the Cherokee Nation. “Although many people appear as intermarried whites on census cards (Cherokees), only 286 persons are on the roll as Intermarried Cherokees because citizenship was granted to only those married prior to 1877,” explains Myra Vanderpool Gormley in Cherokee Connections.2

Applications rarely name the “full-blooded” Cherokee ancestor. The degree of tribal descent is not always given, either. No quantum of Cherokee descent was required for citizenship in the Cherokee Nation (Oklahoma). That information did not appear originally on membership rolls since every member of the Cherokee tribe was entitled to equal rights, and there had been no reason to keep track of degrees of blood—unlike the Eastern Band of Cherokee’s specific quantum and enrollment timeline requirements.

Clearly, many citizens by blood had more Anglo ancestry than Native American. For instance, James C. Yeargin enrolled as a citizen of the Cherokee Nation by his marriage to a recognized citizen by blood, Mary Jane Kinney, who was about one-thirty-second Cherokee.

Despite being labeled “marriages,” these records do not always give an exact marriage date or even the maiden name of the bride. Sometimes two wedding dates for the same couple are found in an application. This simply implies that the couple had married before their arrival and needed an official record of their union in the Cherokee Nation.

Applicants were required to testify about their marital history. The Commissioner asked the applicant about any previous spouses, whether an earlier marriage ended in death or separation, and the Cherokee Nation citizenship status of any previous spouse. Friends and relatives were often called to testify to substantiate the applicant’s claims.

Before the 1870s, many Cherokee-white unions were informal or common law. Though an Act of Cherokee Council passed on 15 October 1855 required a marriage license,3 some couples continued the earlier practice of having a so-called Indian style marriage. Nancy Cordrey‘s application for enrollment was accepted, though it was indeterminate whether or not she and her half-Cherokee husband had legally wed. Her stepson stated that, in 1862, Nancy and Wilson M. Cordrey “commenced living together like people did in them times. I never asked no questions; it was a general rule that people lived together.” And a minister named Joe Fox recanted his earlier testimony about James Wright and Hattie Hall‘s marital history, clarifying that they “took up and lived together” and had “two, or three, or four” children before marrying.

Some divorces were informal, too. In Mary J. Catron‘s application, Martin A. Wallace testified:

When I came to this country in ’71, there were no divorce law among the Indians, nor no marriage law. They just courted the woman and if she agreed they lived together, and when they got tired they quit.

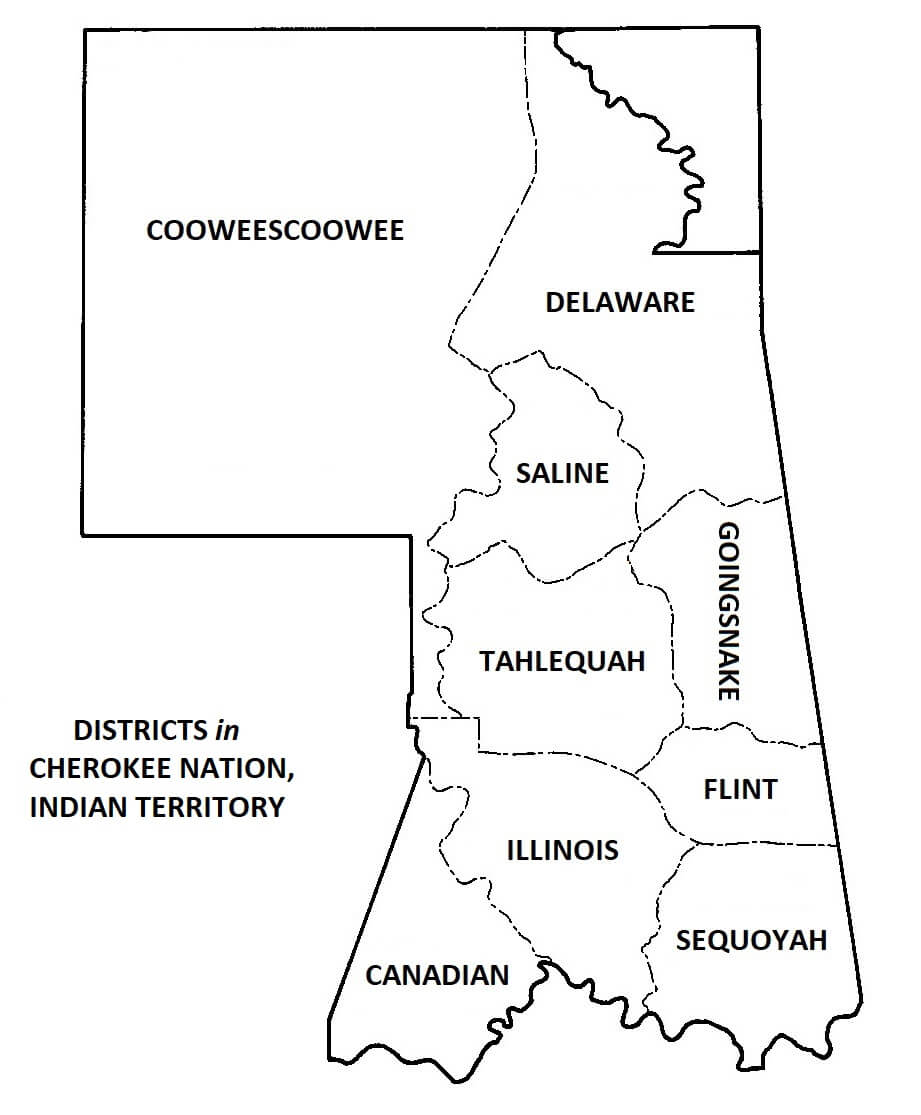

Contrary to Wallace’s claim, the district courts of the Cherokee Nation had jurisdiction over divorce suits. A legislative act approved at Tahlequah, Cherokee Nation, in 1859, stated that, “divorces shall not be granted for any other cause than adultery, or willful neglect of the duties of the married state, by either husband or wife.”4

The type of data found in applications varies greatly. Actual birth dates are rarely given, but ages were always recorded. Applicants were required to state their address, marital status, whether or not he or she was a citizen by blood or intermarriage, the spouse’s citizenship status, and the names of others included in the application for enrollment. In most cases, only children under the age of twenty-one needed to be named. Otherwise, adult children had to file their own papers for membership status. Other inquiries might be tailored to the case. In these instances, the Commissioner might ask for the names of the applicant’s parents or in-laws. For example, the application of Joseph H. Alexander (born ca. 1841) states that his parents were Silas Alexander and the former Mary Kennedy or Kannady. Joseph H.’s wife, the former Sophronia E. Duncan, is identified as the daughter of a Cherokee named John Duncan and Besty, whose maiden name was not given.

The data provided in these applications—verbatim testimony—is a genealogical treasure trove.

Available as Applications for Enrollment of the Commission to the Five Civilized Tribes, 1898-1914, National Archives micropublication M1301, rolls 305, 306 and 307, this genealogical data was abstracted as an eleven-part series in American Genealogy Magazine, Volumes 10, No. 1 thru Vol. 13, No. 3, now freely available as scanned images in a PDF viewer, as found on the links below:

- Cherokee-White Intermarriages, Part I

- Cherokee-White Intermarriages, Part II

- Cherokee-White Intermarriages, Part III

- Cherokee-White Intermarriages, Part IV

- Cherokee-White Intermarriages, Part V

- Cherokee-White Intermarriages, Part VI

- Cherokee-White Intermarriages, Part VII

- Cherokee-White Intermarriages, Part VIII

- Cherokee-White Intermarriages, Part IX

- Cherokee-White Intermarriages, Part X

- Cherokee-White Intermarriages, Part XI

_______

- This was an amendment to the Dawes Act of 1887, a breakup of the tribal government in Indian Territory and subjected all persons in that territory to federal law. Charles J. Kappler’s Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties, Vol. I (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1904), p. 98, quotes Section 21: “That in making rolls of citizenship of the several tribes, as required by law, the Commission to the Five Civilized Tribes is authorized and directed to take the roll of Cherokee citizens of eighteen hundred and eighty (not including freedmen) as the only roll intended to be confirmed by this and proceeding acts of Congress, and to enroll all persons now living whose names are found on said roll, and all descendants born since the date of said roll to persons whose names are found thereon; and all persons who have been enrolled by the tribal authorities who have heretofore made permanent settlement in the Cherokee Nation whose parents, by reason of their Cherokee blood, have been lawfully admitted to citizenship by the tribal authorities, and who were minors when their parents were so admitted; and they shall investigate the right of all other persons whose names are found on any other rolls and omit all such as may have been placed thereon by fraud or without authority of law, enrolling only such as may have lawful right thereto, and their descendants born since such rolls were made, with such intermarried white persons as may be entitled to citizenship under Cherokee laws. It shall make a roll of Cherokee freedmen in strict compliance with the decree of the Court of Claims rendered the third day of February, eighteen hundred and ninety-six.”

- Myra Vanderpool Gormley, Cherokee Connections: An Introduction to Genealogical Sources Pertaining to Cherokee Ancestors (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., 1995), p. 31.

- Laws of the Cherokee Nation, Passed During the Years 1839—1867, Compiled by the Authority of the National Council (St. Louis: Missouri Democrat Print, 1868), pp. 104-105, which states: “any unmarried white male wishing to marry a Cherokee woman was required to obtain a marriage license from one of the district courts in one of the several districts, provided he had first paid a fee, taken an oath to the Cherokee Nation, and presented the district clerks with “a certificate of good moral character, signed by at least seven respectable Cherokee citizens.”

- Ibid., p. 48.

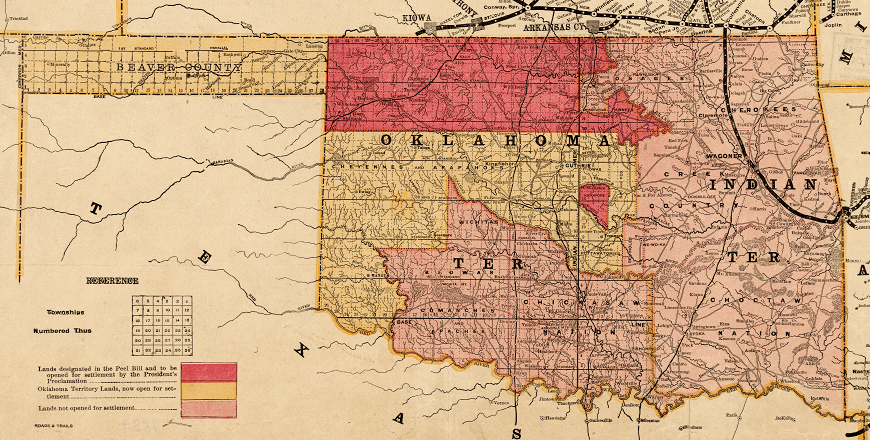

H. C. Townsend, A Correct Map of the Oklahoma Country and Cherokee Outlet Reached via the Missouri Pacific Railway and Iron Mountain Route (1889)

Visit our online bookstore, Jacobus Books